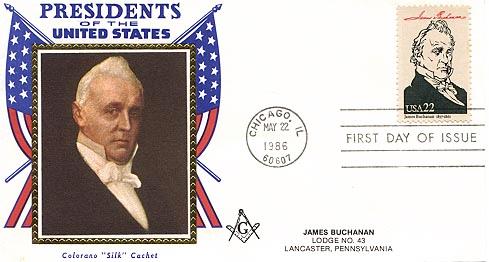

James

Buchanan

Fifteenth

President of the United States

James Buchanan, the 15th

PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES (1857-1861), served during the beginning of the

secession crisis that led to the Civil War. Of Scottish-Irish descent, he was

born on Apr. 23, 1791, in Cove Gap, near Mercersburg, Pa., the son of James

Buchanan, a prosperous storekeeper, and his wife, Elizabeth Speer.

Young James received an academy education and attended Dickinson College,

Carlisle, Pa., graduating in 1809. He then studied law in Lancaster, where he

began practice in 1813. Although a FEDERALIST in political sympathies, he

supported the prosecution of the War of 1812 and participated as a volunteer

in the defense of Baltimore.

After serving in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives (1814-16), Buchanan

devoted attention to his law practice, which soon prospered. In 1819 he became

engaged to Ann Coleman, daughter of a wealthy Lancaster iron manufacturer, but

as a result of a misunderstanding the engagement was ended. Her sudden death

shortly thereafter left Buchanan desolate. He never married.

In 1820, Buchanan was elected to the U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. With the

collapse of the Federalist party, he supported Andrew JACKSON for the

presidency. In the late 1820s he emerged as the leader of the Amalgamation

party, the dominant faction of Pennsylvania Jacksonians.

Buchanan retired from CONGRESS in 1831 but later that year accepted Jackson's

offer of the ministry to Russia. He remained at St. Petersburg from 1832 to

1834, where he concluded a commercial treaty. Shortly after his return he was

elected to the U.S. SENATE, where he served from 1834 to 1845.

Mentioned as a possible

presidential candidate in 1844, Buchanan became (1845) secretary of state in

the cabinet of President James K. POLK. Although Polk personally directed the

formulation of foreign policy, Buchanan worked diligently in matters relating

to the consummation of the annexation (1845) of Texas, the settlement of the

Oregon Question, and the Mexican War. He retired from office at the end of the

Polk administration in 1849. Buchanan was a serious contender for the

DEMOCRATIC nomination in 1852 but lost to Franklin PIERCE, who named him

minister to Great Britain. His mission in London (1853-56) accomplished little

but benefited him politically, for he remained aloof from the controversy over

the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854).

At the Democratic convention in

1856, Buchanan won the presidential nomination on the 17th ballot. In the fall

he won an ELECTORAL victory, although he failed to get a popular majority over

John C. Fremont, the Republican, and Millard FILLMORE, the KNOW-NOTHING

candidate.

Two days after Buchanan's

inauguration, the Supreme Court declared in the Dred Scott case that Congress

had no power over slavery in the territories. He welcomed this ruling as

the final word on that issue, but the REPUBLICANS and many Northern Democrats

refused to accept the Court's opinion. Like Pierce, Buchanan met difficulties

in organizing Kansas Territory. He urged Congress to accept the territory's

proslavery LeCompton Constitution, even though it had been drawn up by an

unrepresentative convention that had refused to submit it to the people.

Stephen A. Douglas, Democratic senator of Illinois, broke with Buchanan,

arguing that the president's stand made a mockery of the doctrine of Popular

Sovereignty. Ultimately the constitution was referred to the Kansas

electorate, which overwhelmingly rejected it.

With his long experience in

diplomacy, Buchanan expected his administration to conduct a vigorous foreign

policy. He sought to extend American influence in the Caribbean, but

congressional opposition forced him to give up efforts to purchase Cuba from

Spain. Inevitably, domestic matters intruded upon his attention. The panic of

1857 added to the unpopularity of his administration and contributed to heavy

Democratic losses in the congressional elections of 1858.

The sectional controversy grew

steadily more serious during the last two years of Buchanan's presidency. The

raid by John Brown at Harpers Ferry and Brown's execution by Virginia

authorities in 1859 intensified public feeling in both the South and the

North. In the presidential campaign of 1860 the Democratic party split, and

Buchanan endorsed Vice-President John C. BRECKINRIDGE of Kentucky, whom he

considered the regular nominee, instead of Douglas, the candidate of the

Northern Democrats.

The election of Abraham LINCOLN,

the Republican candidate, prompted the secession of seven Southern states and

the creation of the Confederate States of America during Buchanan's last

months in office. The president was criticized by secessionists because he

denied the legality of their action and by Northern advocates of a more

vigorous policy because he believed that the executive lacked the power to

coerce a state. He based his hopes for the survival of the Union on

last-minute compromise efforts, which failed. As the more pro-Southern cabinet

members resigned during the crisis, he took a stronger pro-Union stand,

refusing to turn over Fort Pickens in Florida and Fort Summer in South

Carolina to the authorities in those secessionist states.

During the Civil War Buchanan

generally supported Lincoln's war policies while preparing a defense of his

own administration, which he published in 1866. He died at his estate,

Wheatland, near Lancaster, on June 1, 1868.

Buchanan's reputation is judged

mainly by his conduct during the last months of his presidency, and he is

therefore generally regarded as an ineffective executive. In his defense it

can be said that he was a lame-duck president caught in a vicious crossfire

between secessionists and Republicans. But at the same time his adherence to a

conservative legalism led him to interpret narrowly his powers to deal with an

unprecedented constitutional crisis.